Aggregated, for better and for worse?

A few thoughts on aggregation, after a summer marked by a series of agreements.

Moving day is here for the audiovisual industry. The flurry of agreements between VOD services, making one's catalogue available on the other's service, is reminiscent of the Quebec custom known as "Moving Day," that one day when thousands of tenants all move at the same time, in a joyful cacophony. It seems that audiovisual companies have also decided to sign new residential leases, all practically at the same time. Last November, TF1 announced that Arte would be available on TF1+. Then in June of this year, it was Netflix's turn to announce that TF1 programs would be available on its service, starting in the summer of 2026. Barely a month later, Amazon and France Télévisions agreed to make public-service programs available on Prime Video. Disney+ is also getting in on the game and signed partnerships this summer with ITVX in the UK and ZDF for Germany, Austria, and Switzerland.

The buzzword for the second half of the year will therefore be "aggregator." This word, originally used in IT, should not be confused with its other use in the audiovisual industry, which refers to companies that "distribute" content to VOD services. They handle uploading and enriching metadata, most often for transactional exploitation. In this article, an aggregator is defined as an on-demand video service that provides access to one or more third-parties' catalogues, possibly on top of its own catalogue.

Aggregation is not new—in France, Molotov and myCanal have been doing it for years—but the phenomenon has gained momentum in recent months and appears to be accelerating. The new development is that this strategy is now being adopted by international players, including those who have been going it alone until now, and they are now integrating the offerings of local broadcasters. To a certain extent, aggregation as practiced by the VOD giants can be considered an extension of their local production strategy, which translates into a catalogue that feels "close to home". On one hand, the agreements signed with our national broadcasters are small victories because they demonstrate the relevance of their editorial positions, something that the industry giants have struggled to replicate. But viewed from a more pessimistic perspective, these agreements between small local services and large international services give off an air of surrender, perhaps even heralding the end of independence and sovereignty as an objective for local VOD services.

Future historians will undoubtedly interpret the period we are experiencing as a logical continuation of the one we are leaving behind, where everyone believed they could launch their own VOD service, and most of them failed. The streaming wars ended with an overwhelming victory for Netflix, Prime Video, and Disney+, and we are now entering a period when territory is being split, and new borders drawn. For the losers, it is natural to want to conclude a distribution agreement with the winners. "If you can't beat them, join them," as they say.

Looking for well-located homepage, preferably first rows

There are several types of aggregation and just as many different relationships between the aggregator and the aggregated, but the central concern is always the same: the position of the third-party service's offering on the aggregator's interface. To classify the different types of aggregation, let's return to our housing analogy:

- The Rental - The tenant has a space they can arrange as they wish.

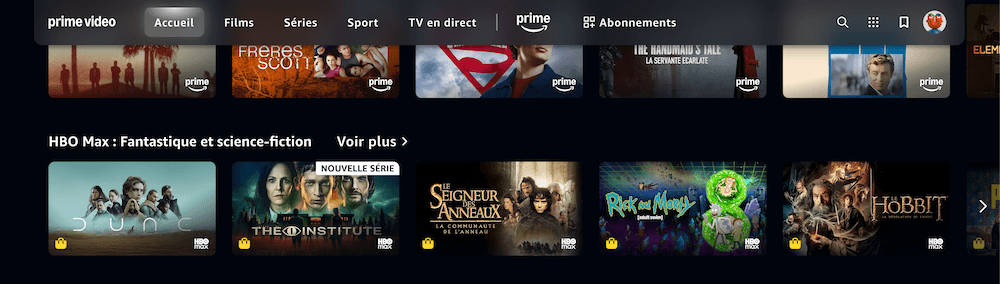

Here, the third-party service's catalogue is given a dedicated space on the aggregator's interface. This space can take the form of one or more themed rows, a section on the home page, or even a separate page. Most often, the publisher of the aggregated service is free to curate their space by choosing which titles to highlight and determines the order in which they appear.

Example : Prime Video

- The Homestay - The tenant occupies a room and shares common spaces with the owner.

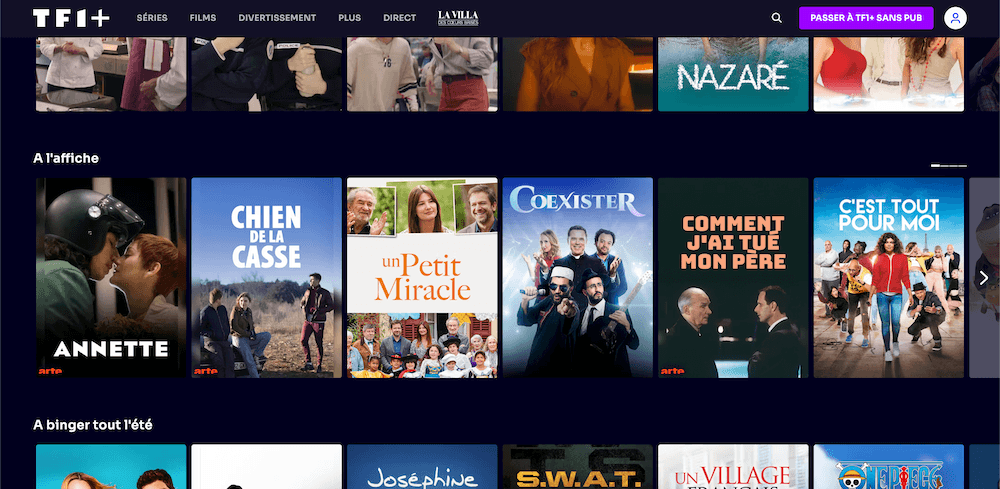

In this case, the aggregated service's content is mixed with that of the aggregator service. The titles from both can appear side-by-side, for example, within the same themed rows or carousels, which does not exclude the possibility that the aggregated service's offering also has its own space.

Example : Arte on TF1+, and presumably TF1 on Netflix in 2026.

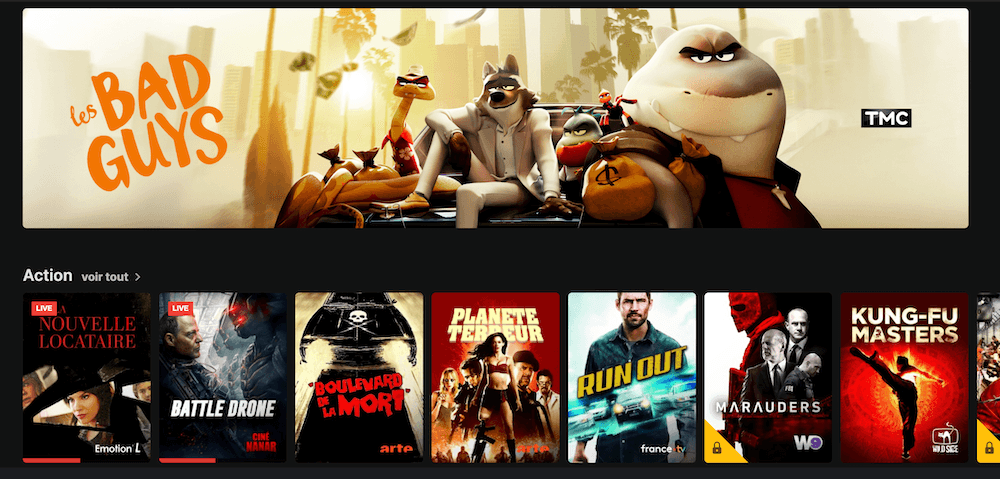

- The House Share - Several tenants share the same living space.

The aggregator does not offer its own catalogue, and all the content is therefore made up of titles from third-party services. Their placement on the interface can be decided arbitrarily or monetized by the aggregator (by paying more, you can get a better room!).

Example: Molotov, ISP box interfaces (Free, SFR, Bouygues, etc.), Google TV if you don't count YouTube.

At first glance, and this applies to all the variations above, aggregation is a "win-win" operation. On one hand, the aggregated service gains new exposure to the aggregator's existing users, who are often more numerous or constitute a demographic target coveted by the aggregated service. On the other hand, the aggregator increases the attractiveness of its content offering by diversifying it or simply increasing its volume. The aggregator may even gain users from the aggregated service by persuading some to now watch on its app or by introducing these newcomers to the rest of its catalogue.

"Discoverability" is a word that, like "aggregator," has made a recent appearance in audiovisual jargon. A concept from Quebec, it refers to the "ability of content to be discovered," and it finds its full meaning in the context of aggregation.1 For the aggregated service, being available on a new distribution channel mechanically increases the discoverability of its offering. Depending on the agreement with the aggregator, the aggregated service can even retain some editorial control over the titles that are most discoverable. In this case, it is free to adopt specific prominence strategies for this distribution channel, for example, to precisely target the aggregator's subscribers or simply to experiment with curation techniques that can be replicated later on its own service. However, these two examples illustrate the need for the aggregated service to have access to usage data, which is an important point in any digital distribution agreement negotiation.

The benefits of aggregation are numerous, and it seems difficult today for a "small" service—one that targets a single territory or deals with a single theme—not to ride the wave. But the current enthusiasm for aggregation can almost make us forget the adage, universally accepted until recently, that "the medium is the message." So, what message does the availability of France.tv on Prime Video or Arte on TF1+ send? Can the brand image of the aggregated service be altered or even weakened by its new medium? It may be too early to comment on the strategy of our local broadcasters, but the operation is certainly not neutral. What's more, television viewers have transformed into users. Where the viewer used to navigate on a rather neutral medium (numbered channels, the FM band), the user today browses on a medium already associated with a brand, that of the container (here, Prime Video or TF1, for example), which is potentially different from that of the content (France TV, Arte) and, above all, is to some extent its parent in their eyes. When the aggregator offers its own programs in addition to those of the aggregated service, it is difficult not to consider the third-party service's offering as secondary to that of the host service. The difference between Arte on YouTube and Arte on TF1+ lies in the user's perception of YouTube and TF1+, respectively. YouTube is a UGC platform that, in the user's eyes, offers a neutral catalog where Arte programs sit alongside amateur videos. TF1+, on the other hand, is a curated service, still associated with the linear channel. Arte on TF1+ therefore implies a relationship of editorial subordination that cannot exist on YouTube.

This is why, to return to our housing analogy, it is essential for an aggregated service to have a main residence, meaning its own distribution channel, identified by the public as both the point of origin of its offering and where it "lives" primarily. For example, there is no doubt that France Télévisions' digital content offer is available first and foremost on the france.tv service, which is both a website and an application. The same goes for the BBC in the UK, whose iPlayer has hosted its online catalogue since 2007. In this case, the brand image is not necessarily weakened by aggregation, and the appearance of a dedicated section for the aggregated service's offering on the aggregator's interface acts more as a preview of what's happening elsewhere.

Some players are therefore better suited than others for the aggregation game. The characteristics we have identified for "passing the aggregation test" are as follows:

- A strong, independent presence elsewhere on the internet and/or via mobile and TV apps. This is the main residence we just mentioned, essential for not diluting its brand image.

- A unique offering that is different from that of the aggregator. The idea here is that the user should be able to identify the service's row by the content it offers, and not only by its title. Typically, a service that offers mainstream films and series is not suitable for aggregation because it will be editorially crushed by its aggregator.

- An offering that highlights its natural proximity to its audience, something that is more difficult for the aggregator to achieve, as it is most often an American company present in many territories. Example: The INA's Madelen service on Prime Video.

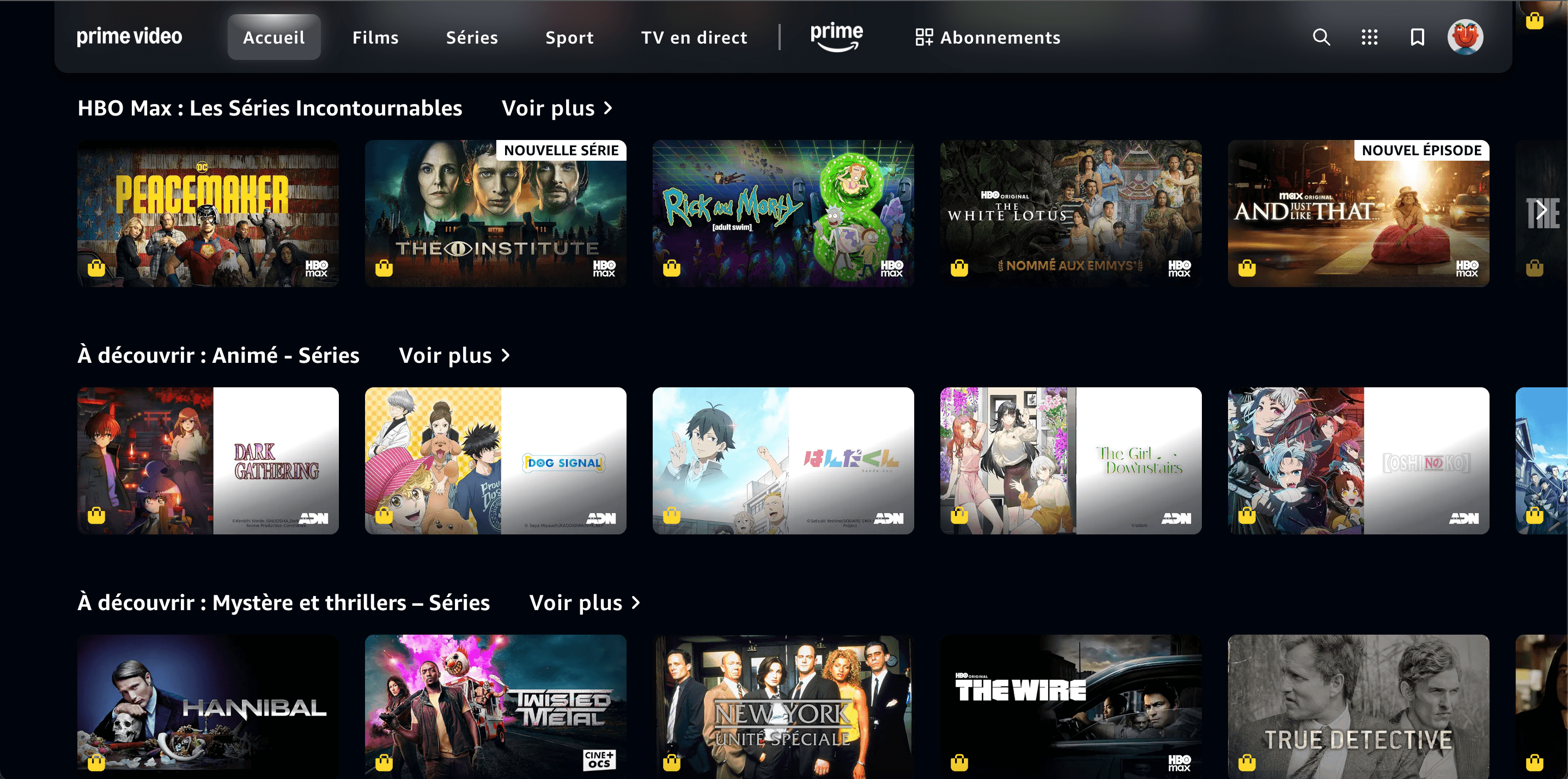

- A strong ability to curate. Quality over quantity: the aggregator will only entrust the service it distributes with a small number of thumbnails on its homepage. What's more, algorithmic recommendation is often less important for third-party services. They can choose which titles to highlight and should take advantage of this.

- It may seem trivial, but it is essential that the thumbnails are "stamped" with the aggregated service's logo.

The most striking example: Anime Digital Network on Prime Video, whose thumbnail style contrasts with that of the other rows, making them instantly discoverable.

Conclusion

Increasingly, being aggregated will involve a delicate cohabitation with content from distant planets: those strange beasts that are video games (Netflix), sporting events (Prime Video), or even amateur videos (YouTube on Google TV). To be seen, it's no longer enough to be available; you also have to be discoverable. However, the homepage imposes both a strict hierarchy (vertical and horizontal) and a uniformity in presentation, with all formats arranged side-by-side in rectangular thumbnails. In this environment, a third-party service must be ready to elbow its way to the "prime-space," those areas where the user's gaze is primarily directed. Aggregation can certainly be a good thing, but only if the aggregated service's catalogue finds a proper place on the host service.

Notes

- ↑

The concept of discoverability also applies to the positioning of apps on Smart TV menus for example, and even to shortcut buttons on remotes.