Deezer and its challenges

Between fragile profitability and subscriber quest, what's next for Deezer in tomorrow's streaming economy?

After years of decline, the recorded music market returned to growth almost a decade ago, driven by subscription streaming which now accounts for nearly 70% of revenues. Yet, Deezer, celebrating its 18th anniversary this summer, is struggling to find its place within this dynamic. While the company announced its profitability last year, hinting at good results for 2025, its latest quarterly results paradoxically show a significant loss of subscribers.

Behind the tree of profitability lies a forest of major challenges weighing on its growth levers. Firstly, acquiring new subscribers is particularly expensive in a sector where public willingness to pay for a subscription has been severely eroded by years of piracy. This reality directly clashes with the quest for profitability, which demands drastic cost reductions in a highly competitive market where some players have almost unlimited financial resources.

However, some trends are promising: the low market penetration of streaming suggests good growth prospects, and the probable evolution of the music streaming economic model towards a more hybrid approach, mixing subscriptions and direct-to-fan transactions, could allow for better artist remuneration, while increasing the margins of pure players.

From initial chaos to national flagship

It's hard to talk about Deezer without mentioning the major crisis that hit the music industry at the dawn of the 2000s. The advent of the Internet and massive piracy caused an economic model traditionally based on record sales to collapse, with revenues plummeting by 80% in a decade. It was in this chaotic context that the idea of a legal and free, advertising-funded offer emerged. This initiative was made possible by an initial investment from Xavier Niel and a foundational agreement with Sacem. However, this economic model, exclusively driven by advertising revenue, proved to be a dead end for Deezer, which indeed took longer than Spotify to adopt the two-sided model we know today, combining a free, ad-funded offer with a paid subscription. One of streaming's promises then was to curb piracy, and although this goal has been partially achieved, illegal practices unfortunately remain prevalent.

After a laborious start,1 its ascent became meteoric, propelled by a decisive strategic alliance forged with Orange in 2010. By becoming the default service for millions of the operator's subscribers, Deezer established its dominance in the French market until 2019. However, the path to economic maturity proved more complex. An initial attempt at an IPO was aborted in 2015, but it nevertheless confirmed its potential by becoming a "unicorn" in 2018, with a valuation exceeding one billion dollars following a €160 million fundraising round. The IPO was finally successful in 2022, but the market's sanction was swift. Despite disappointing results and a collapsed share price, this operation nevertheless allowed Deezer to raise the €143 million needed to pursue its ongoing goal of achieving profitability. To this day, Deezer's capital is predominantly held by the American investment firm Access Industries (36.8%), which notably owns Warner Music Group.

This period in the music industry's history, first marked by the normalisation of piracy, then by the arrival of free, ad-supported offers, ingrained a culture of gratuitousness in people's minds. This is why the monetisation of the subscription model remains extremely arduous today, as Alexis Lanternier, Deezer's new CEO, recently stated in Billboard: "Paying this price to access all the music in the world amounts to underestimating it."2 While this question of the "value" of music, both economically and culturally, has long been the subject of rich academic literature and fierce industry debates, it now contributes to a broader reflection on what should be "fair" remuneration for artists within an increasingly platform-dominated ecosystem.

What is Deezer worth today?

In 2024, Deezer recorded a turnover of €542 million, an increase of 11.8% compared to 2023. This performance reflects notable growth over ten years, as turnover was only €141.9 million (current euros) in 2014, representing a progression of over 280%. However, this growth appears modest when compared to Spotify, whose turnover rose from one billion to nearly €16 billion over the same period, representing an increase of over 1441%. Deezer's revenues mainly come from direct subscriptions (64%) and partnerships (31%), with advertising contributing only 5%. Geographically, France accounts for 58% of turnover, with the rest of the world contributing 42%.

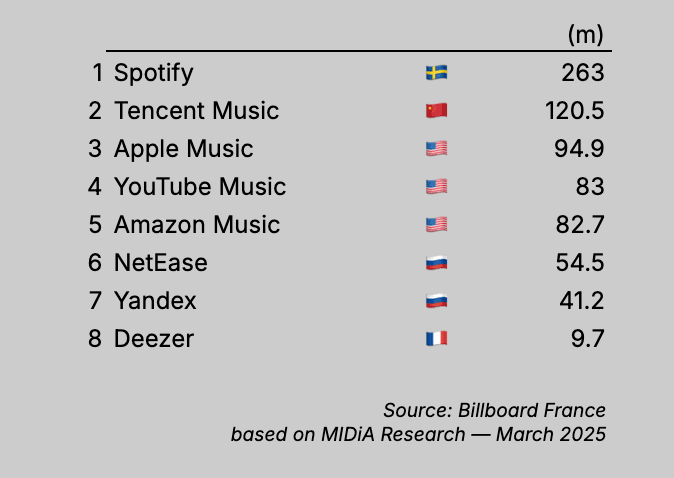

On the subscriber front, Deezer had 9.5 million users in Q1 2025, marking a loss of approximately one million compared to the previous year. Despite this recent setback, the platform has still seen its subscriber numbers increase by 40.58% over a decade compared to the 6.9 million recorded in 2014. At that time, the gap with Spotify was far less pronounced: while Deezer had 6.9 million subscribers, Spotify had 15 million. Today, the gap has considerably widened, with Spotify totalling 263 million subscribers. In its domestic market, Deezer's position has also significantly eroded, falling from a 45% market share in France in 2014 to 24% currently, while Spotify has taken the lead with around 45%. Today, Deezer ranks as the 8th largest global service by subscriber numbers according to Billboard, citing figures from MIDiA Research's latest report.

Unlike services integrated into vast technological ecosystems like Apple Music or Amazon Music, "pure players" such as Deezer and Spotify struggle to achieve robust profitability. This difficulty is primarily due to the low margins they manage to generate. Last year, Deezer's gross margin was 24.7%, while Spotify's reached 30.14%. This situation is explained by the very structure of their economic model: most of their turnover is absorbed by external costs, with approximately 70% paid to rights holders and 10% taken by app stores. Far from a simple direct exchange between a subscriber and a platform, the music streaming economic model relies on a Kafkaesque system of revenue redistribution, involving multiple actors bound by different types of contracts, most often confidential, with calculation rules that can vary according to the nature of the listening (voluntary, passive, algorithmic, etc.). The widening margin gap between the two platforms is notably linked to the renegotiation of their agreements with labels and publishers; for example, Spotify concluded a new agreement with Universal Music Publishing in early 2025 as part of its highly publicised "Streaming 2.0" strategy, aiming to improve its gross margin.

To improve its profitability, Deezer is exploring double-edged strategies. On the one hand, it relies on partnerships with telecom operators or third-party services to temporarily boost its user base, such as the agreement with Mercado Libre in 2023. While this approach quickly attracts subscribers, converting these free trials into paid subscriptions remains a challenge, and low conversion rates impact long-term retention, as evidenced by the net subscriber loss last year. On the other hand, the markets targeted by these partnerships are generally countries where the subscription price is much lower, which significantly reduces the average revenue per user. Finally, drastic reductions in structural costs, notably through staff cuts, have become unavoidable. Following Spotify, which laid off 17% of its employees in 2023, Deezer also reduced its workforce by 6% last year, returning to its 2021 employment level.

The company is therefore facing a true balancing act: developing its subscriber base requires investment, while the pursuit of profitability demands cost reduction. This dynamic raises a fundamental question about the value of music and the viability of a system that seems to favour labels, placing artists and platforms – despite being creators of value – in an economically disadvantaged position. As Matthew Ball analysed in 2018: "A huge portion (if not the majority) of value is created by artists and the streaming services, but most of the proceeds are captured by the labels."3 This reality has not escaped some artists who, like Taylor Swift buying back the master rights to her first six albums, are increasingly seeking to break free from contracts with major record labels, foreshadowing greater disintermediation in the years to come.

And tomorrow?

The music streaming market is generally far from saturation, thus showing strong growth potential. IFPI data4 highlights a large margin for progression, particularly in France, where the paid subscription penetration rate is only 25.9%. The country lags behind Germany, the UK, and especially the Nordic countries, which boast a very high adoption rate of 55%, an increase of 2 points since 2022.5

In France, the Arcom study on audio-video trends,6 published last April, confirms these observations and highlights the music industry's monetisation challenges. Only 40% of households use a paid audio streaming service, with a median monthly expenditure of €12. This contrasts sharply with the audiovisual sector, where 73% of French people subscribe to at least one paid offer for a median monthly expenditure of €20.

These disparities reveal a very different perception of value and monetisation capacity between the two industries. This largely explains why the nature of the content is different. Subscribing to an audiovisual service provides access to a catalogue of premium and exclusive content, which encourages multiple subscriptions. It is common to subscribe to different platforms such as Netflix for Stranger Things, Disney+ for Andor, or HBO Max for The Last of Us, making subscribers more versatile. In the music world, the dynamic is different: despite data portability, changing platforms is not as easy, and content exclusivity is not as powerful a factor. Although music platforms have explored this path in the past (Spotify with Joe Rogan's podcast, Deezer with its Deezer Originals like the Souvenirs d'été 2018 cover album), these initiatives have not fundamentally changed user habits or their perception of value compared to the overall catalogue.

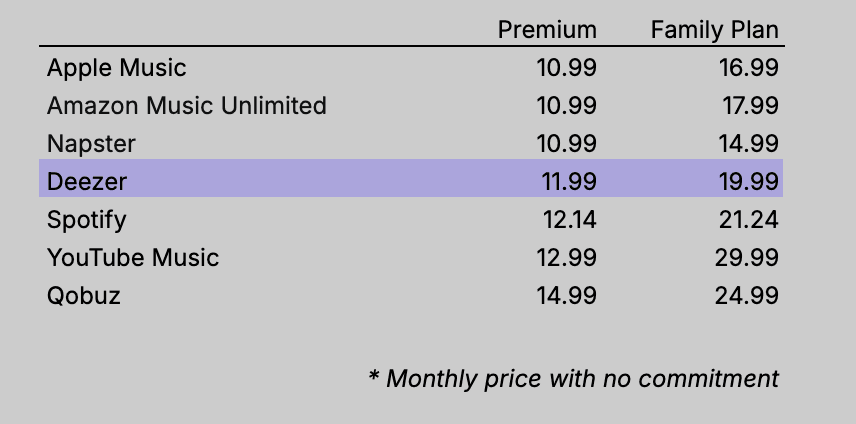

Facing this context, the music streaming sector is exploring new strategies. One avenue being considered is to increase the average revenue per user (ARPU) by adjusting subscription prices. Netflix, for example, successfully raised its rates as user penetration and engagement grew, but it could do so by relying on more stable licensing costs, allowing it to increase its margin as its revenues grew. For music streaming, the situation is different because, unlike Netflix, an increase in subscriber numbers does not automatically lead to a proportional increase in revenue. Indeed, royalty costs are directly linked to listening volume. However, the main lever for market penetration, family subscriptions, drives down per-stream rates, drastically reducing ARPU. Thus, a Deezer family subscription, offering six profiles, brings the cost per user down to just €3.3, a price difficult to sustain in the long term. Recently, YouTube Music opted for a 25% increase in its family subscription, bringing it to nearly €30 per month.

Another promising avenue is the evolution towards a hybrid model, combining traditional subscriptions with new forms of direct-to-fan monetisation, thereby encouraging greater disintermediation. This is the direction Spotify seems to be taking, with the hypothesis of a "super premium" subscription, as recently reported by the Financial Times.7 The example of OnlyFans illustrates the potential of this model: the platform paid out $5.3 billion to creators in 2023, an impressive figure compared to the €2.4 billion in recorded music trade revenue in the same year. However, even if the low penetration rate of the French market suggests room for growth through price increases, this strategy could intensify competition with integrated players like Apple Music and Amazon Music, who are able to maintain lower prices thanks to their vast ecosystems.

Conclusion

For Deezer, the announcement of profitability is good news and has certainly helped to reassure investors. However, the service's strategic identity in the medium term remains to be defined. Its current position places it closer to a niche player like Qobuz than a generalist giant like Spotify, which raises a crucial positioning challenge in this rapidly changing competitive market. Deezer's current differentiation, based on a more ethical and proactive stance, is certainly commendable, but it is unlikely that this alone will suffice to massively attract new subscribers. Nevertheless, it represents a necessary battle to transform a system deemed inequitable.

Notes

- ↑

To find out more about the birth of Deezer and its background, you can read journalist Philippe Astor's article on the CNM website, published on 10 April 2020 [IN FRENCH]. Available online.

- ↑

Zoé Thouvenin (2025). Alexis Lanternier: ‘To pay this price to access all the music in the world is to underestimate it’. Billboard France, 20 June 2025. Available online.

- ↑

Matthew Ball (2018). 16 Years Late, $13B Short, but Optimistic: Where Growth Will Take the Music Biz. Available online.

- ↑

Bilan 2025 available on the SNEP website.

- ↑

Tim Ingham (2024). A warning sign? Sweden has fewer paying music subscribers than it did 2 years ago, according to YouGov survey. Music Business Worldwide, 27 juin 2024. Available online.

- ↑

Arcom (2025). Tendances audio-vidéo 2025. Available online.

- ↑

Anna Nicolaou (2025). « Spotify to launch new premium service aimed at music ‘superfans’ ». Financial Times, 15 février 2025. Available online.